Committee Blog: Interstate Commerce – Breaking the Laws of Economics (Part 3)

By Gabe Cross and Gary Seelhorst

Members of NCIA’s State Regulations Committee

Legal cannabis, for all of its promise, has failed – in some markets spectacularly – to live up to its economic potential. But while each self-contained state market faces its own combination of political and regulatory challenges, the core of the problem everywhere is basic economics. Legal markets exist to efficiently move goods from where they are best produced to where there is the greatest demand. But cannabis, straddling the line between emerging state regulation and the remnants of federal prohibition, has negotiated that legal chasm by violating the inviolable laws of supply and demand, with predictably disappointing results. Perhaps now, in the face of a disastrous recession, with legal and legalizing states in desperate need for jobs and economic stimulus, is the time to get it right by allowing licensed commerce between legal markets.

The inability to move cannabis across state lines creates myriad problems for legal cannabis market operators that have far-ranging effects for all stakeholders in the cannabis industry, from investors to employees down to the patients and consumers who use the end products. The hindrance to economic activity also slows economic growth, employment, and tax revenues to states that have legal cannabis sales.

Oversupply Vs. Undersupply

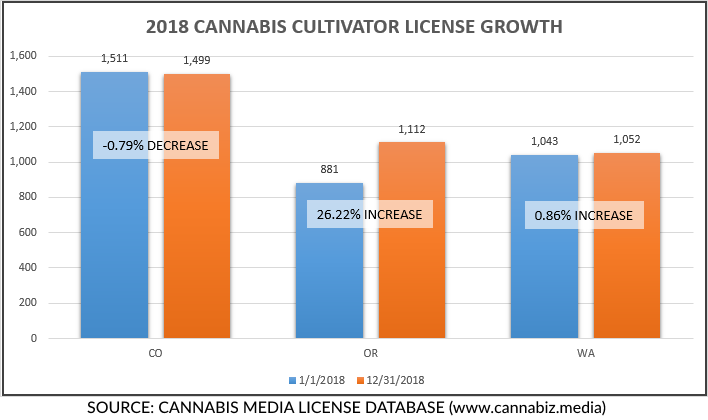

Oversupply of cannabis in states like Oregon, which has excellent growing conditions and a favorable regulatory environment, are completely artificial and created not by the true excess of cannabis, but by the current inability to export to more populous states. This oversupply causes prices to plummet, which benefits consumers in the short term but is disastrous for small and medium-sized businesses and has far-reaching impacts on the communities that rely on this agricultural cash crop. Long term, the effect of these artificially low prices is that small businesses fail and large businesses take their assets to scale, which reduces employment and revenues in the communities that produce cannabis and extract the profits for investors in the large firms. This reduces competition and diversity in the industry, which hurts the same consumers in the long run who briefly benefited from the low prices. This is not a theoretical or academic argument, as we have seen these exact dynamics play out in Oregon over the past three years, with a staggering failure rate and rapid consolidation across the industry. Hundreds of millions of dollars of local capital have been eradicated as small businesses funded by friends and family have been forced to sell out to larger operators just to cover the worst of their debts.

In states which experience undersupply of cannabis, whether due to poor growing conditions or unfavorable regulations (or both) prices rise, hurting legal customers and patients of state-legal operators right away. Businesses can ultimately suffer losses of potential revenue, even as prices climb when consumers turn to cheaper cannabis from the illicit market. This undermines the legal systems set up by these states and pushes consumers to less-safe, unregulated products. As consumers drift from the legal to the illicit market, again the small and medium-sized businesses that currently represent the majority of the industry become financially unsustainable will suffer most, with the same end result to cannabis stakeholders as an oversupplied market.

Meanwhile, the artificial boundaries make scaling a business nearly impossible without access to an unlimited pool of capital. If a company from Washington, for example, wished to scale up and access new markets, they would have to completely recreate their entire supply chain, and most of their administrative operations, equally increasing their overhead with physical space and labor, for each new state that they wanted to enter. Effectively, they would have to create a brand-new small business in each state instead of scaling their operations efficiently and just expanding sales efforts to new territories. This is complicated in the extreme, both logistically and financially. What is worse, those redundant operations will become completely obsolete when cannabis is de-scheduled and interstate commerce allowed. This will almost certainly lead to a mass lay-off in the cannabis industry for all multi-state operators seeking to consolidate their operations. This will improve their cost competitiveness and further accelerate price drops that particularly hurt small businesses and stakeholders across the industry.

In fact, the extreme difference between the current state of the industry and a future in which interstate trade is allowed creates perverse incentives to investment, as opportunities that may be attractive in the short-term will ultimately prove disastrous long term. For example, massive energy and water-intensive indoor growing operations would be needed for New York to supply its population locally, and those facilities would require billions in investment dollars. These investments would look fantastic if one could be assured that the current regulatory environment would not change. But, if de-scheduling or other federal action allows for interstate trade, these facilities would have only a few years to reap the benefits of high margins before having to compete on cost with cannabis grown outdoors in the fertile Emerald Triangle of Northern California and Southern Oregon, which can produce much larger quantities of high-quality cannabis with a fraction of the inputs.

Newly legal net consumption states like New York and New Jersey will struggle to match supply to demand for years after initial legalization, resulting in millions of dollars of lost revenue, lost employment opportunity, and lost tax collections as the state struggles to develop the capacity to meet demand in a place that has no history of large scale production. If states that have historically been net importers plan for interstate trade from the outset, they can have a thriving retail industry with fully stocked shelves by taking high-quality products from producer states like California, Oregon, and Colorado within months of being able to import. The rapid change from essentially no legal industry to a robust, rich, and diverse retail environment would provide immediate economic stimulus in the form of jobs, thriving small businesses, and tax revenues. If new states are forced to rely solely on cannabis that is grown, harvested, processed, and distributed within state lines, it could take many years to develop the full economic benefits that a legal market could bring to bear.

All of these issues can be avoided, or at least mitigated, by a shrewd approach to incremental interstate trade instead of an instantaneous switch from 25 or more siloed industries to one national, or potentially international, market. The dynamics of how different state regulations interact can be tested and worked out thoughtfully, allowing for a more seamless transition and a clear roadmap for federal regulation when cannabis is de-scheduled. Successful interstate trade on any scale, between even just two states, will clearly signal to investors that the future of interstate trade is of pressing urgency to incorporate into their investment strategy. An investor in New York could then focus on opportunities related to local product development with the promise that affordable raw materials would be available from California and skip investing in indoor agriculture. Consumers and patients in states that allow for trade across their borders will instantly have access to a wider array of products, and as the size of the market that the industry has access to increases the dramatic supply and demand swings will be dampened by a larger and more diverse base of both consumers and producers.

Ultimately, the purpose of markets is to maximize the efficiency and utility of the flow of goods. They should move from the places where they are cheapest to produce to the places where the demand is highest. This is most effective with commodities and consumer goods, like cannabis. The current restrictions against moving cannabis across state lines completely hobble the market’s ability to perform this critical function. The result is bad for producers, consumers, regulators, and state governments. Interstate commerce for cannabis means better markets for producers, more choice for consumers, and a massive economic stimulus for all participating states in the form of job creation and increased tax revenues.

Be sure to check out the first two blogs in this series:

Ending The Ban On Interstate Commerce

Interstate Commerce Will Benefit Public Safety, Consumer Choice, And Patient Access

Gabriel Cross is a Founder and CEO at Odyssey Distribution, LLC, a distributor for locally-owned craft cannabis producers and processors in Oregon. Gabe worked in the sustainable building industry for a decade before starting Odyssey and brings his experience with sustainability and systems thinking to his work in the cannabis industry. Odyssey manages logistics, sales and marketing for boutique producers so they can focus on creating great craft cannabis products for the Oregon market.

Gabriel Cross is a Founder and CEO at Odyssey Distribution, LLC, a distributor for locally-owned craft cannabis producers and processors in Oregon. Gabe worked in the sustainable building industry for a decade before starting Odyssey and brings his experience with sustainability and systems thinking to his work in the cannabis industry. Odyssey manages logistics, sales and marketing for boutique producers so they can focus on creating great craft cannabis products for the Oregon market.

Gary Seelhorst of Flora California has a passion for developing high-quality cannabis products so their most therapeutic effects can be realized. His 25 years in pharmaceuticals and medical devices helps him bring scientific rigor to the cannabis industry. Gary is very active at both the State and Federal level as an advocate for policy reform/higher quality standards. He enjoyed lengthy stints at Eli Lilly and Pfizer (in clinical development and corporate development) and worked with several start-ups developing corporate and compliance strategies. Gary has a B.S./B.A. from UC San Diego in Biochemistry/Psychology, an M.S. in Clinical Physiology from Indiana University, and an MBA from the University of Michigan.

Gary Seelhorst of Flora California has a passion for developing high-quality cannabis products so their most therapeutic effects can be realized. His 25 years in pharmaceuticals and medical devices helps him bring scientific rigor to the cannabis industry. Gary is very active at both the State and Federal level as an advocate for policy reform/higher quality standards. He enjoyed lengthy stints at Eli Lilly and Pfizer (in clinical development and corporate development) and worked with several start-ups developing corporate and compliance strategies. Gary has a B.S./B.A. from UC San Diego in Biochemistry/Psychology, an M.S. in Clinical Physiology from Indiana University, and an MBA from the University of Michigan.

Follow NCIA

Newsletter

Facebook

Twitter

LinkedIn

Instagram

News & Resource Topics

–

This Just In

Member Blog: The Evolving Cannabis Legal & Regulatory Landscape in 2026

How THCa Vapes Are Changing Consumer